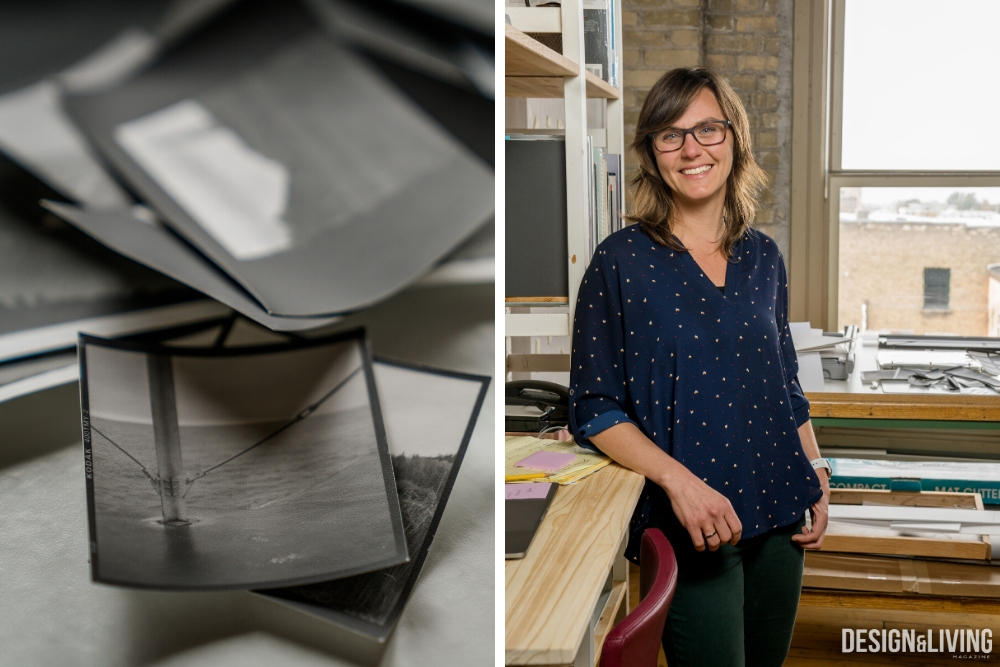

Photos by Hillary Ehlen and provided by Meghan Duda

To identify Meghan Duda as two separate things—an artist and an educator—would be a mislabelling. These two paths are interconnected, mingling and aiding each other, rather than traveling in two parallel paths, as Duda first imagined. “The teaching has become a lot more a part of my process than I think I expected it to. I kind of thought they would travel parallel, my two worlds. But they are much more tied together,” she said. In fact, her office at North Dakota State University also serves as her studio, where mixes of grading sheets interact with photo negatives.

Duda is a photographer, primarily working in film and black and white. She considers her cameras as tools for perception, reinventing how we see nature, cityscapes and horizon lines. Often building her own pinhole cameras, she enjoys exploring how they can capture and perceive light, resulting in atmospheric and abstract depictions.

“In my own work, I prefer analog. I do some digital, but I prefer the haptic nature of being in the darkroom,” said Duda.

When she does shoot digitally, she likes to take an experimental point of view, manipulating her tools and removing some of the expected results. “I feel like when I work digitally, I know what I’m going to get. And when I work analog, I don’t always know what I’m going to get and I like that aspect. The surprise that comes with working with analog,” she said.

While Duda’s world widely revolves around art now, her educational background is in architecture. She graduated from Virginia Tech with an architecture degree but, by the end of the program, she knew she didn’t want to be stuck in an office, as many architect careers require. While she isn’t a practicing architect, influences of this background show in her work and her teaching style.

“I think that is the direction arts education is taking. Like me, I went for a very specific thing, but then life changed. But what I got out of architecture didn’t make me less of an artist, it supplemented it. So how can students have more of a broad idea of what the world can give them? So they’re not pigeonholing themselves leaving school,” she said.

As a professor at NDSU, she teaches the fundamentals of art and design. In this role, she imparts knowledge and inspiration to her students but also uses the platform as an opportunity to try new things herself. “It’s getting [freshmen] comfortable with how to be an artist, beyond just making a really nice drawing. Teaching them how to approach projects and consider an idea,” she said. She instills these creative foundations that encourage students—regardless of if it’s painting or drawing or graphic design— to learn how to produce work that tells a story.

Duda has been practicing this storytelling as of late in her own neighborhood. She has been exploring her neighborhood’s shifting ecology as the Audubon Society embarks on turning empty lots into native prairie ecologies. Duda is interested in this project and knows there is a story to tell about the spaces now inhabitable to humans due to flood zones being given back to nature. “I’m just taking a lot of pictures and trying to figure out how I can tell a story. And what’s the best tool to do it with. All these things I talk to my students about are things that I’m trying to figure out on my own too,” she said. For Duda, she is inspired by asking questions and “what if’s” and letting projects give birth to themselves.

A piece from Duda’s “Trailer Obscura” series hangs in the guest bedroom of her home.

This interest in our ecologies and environmental landscapes is recurring throughout her works. After having grown up on the east coast and attending college in Virginia, she came to North Dakota in 2007. Right after architecture school, she practiced architectural photography, documenting man-made structures. However, her move to the upper midwest introduced her to prairie scenery and her work began shifting away from architecture and toward experimental landscapes. Her pieces took shape into quiet environmental protests, capturing what mankind has done to altered landscapes.

One project of hers that captures her transition from architecture to experimental landscapes is her “Custom Built” series, which she created while in graduate school at the University of North Dakota (2012). The series depicts suburban neighborhood scenes with the homes laser-cut out, leaving white spaces in their absence. “I came in [to the graduate program] photographing architecture, and my graduate professor said, well you’re not allowed to photograph architecture anymore. And so I was like, ha! I’m still going to do it but then I’m going to cut them out!” said Duda. Soon, the rebellious project transformed into more of a statement, as the housing market crashed and the collection became not only a critique of suburbia but a representation of the growing masses of empty houses. “I learned a lot from that process—how an idea can spur so many other conversations,” she said.

This method of asking questions and discovering concepts as she goes along ties into her process and her teachings. “One of the reasons I really like teaching is that experimental aspect. A lot of times, I will have an idea and I’ll want to see how it can be shaped and I’ll actually tie that into an assignment and I’ll see how the students approach it and see how they solve the problems,” said Duda. Creating work alongside her students becomes collaborative. It also becomes a great lesson for the students to see how an idea and process can unfold and evolve.

If you look at Duda’s body of work, no two series are the same. Each project she embarks on is uniquely different from the previous one as she pushes herself to look into new ways to tell a story. From her 5′ x 8′ pinhole camera in a trailer on the prairie to film double exposures downtown to suburban laser-cut scenes, the subjects and methods behind her projects vary from one to the next. To predict what she will produce next is unproductive. In fact, Duda herself might not even know what she is to create next, but the process of uncovering that is what she does best.

In her own home hangs a piece from her Sjællands Odde (2014) series, shot in Denmark.

Meghan Duda

meghanduda.com

Ecce Gallery